By John Hibble

Let’s talk about treasure versus trash, Chinese buried treasure to be exact. How does one go about finding fascinating old things to display in a history museum?

In the good old days, before we had trash trucks and municipal landfills, what did people do with their garbage and trash? They burned it or buried it or, believe-it-or-not, recycled it.

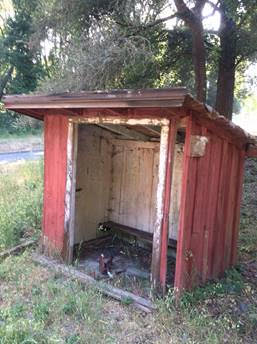

There were several ways to get rid of broken or used pottery, metal cans and glass. It was not uncommon for people to throw trash into bushes or into the forest. Today, we call those people Litterbugs. If you had a house next to a river one could just throw trash out of the window and let the river take it away. It was also not uncommon for people to drop trash or bottles into the privy/outhouse, although that practice would fill up the pit sooner and eventually necessitate the digging of a new pit, so that was discouraged.

The more genteel types would dig a trash pit outside of the kitchen window. Unburnable trash was thrown out of the window into the pit. As the trash and smells built up, a layer of dirt was applied. Once the pit was full you would just dig another. Over time, (a long time), these river banks, privies and trash pits become gold mines of historical artifacts, windows in time.

In the early 1990s, I was a board member of the Santa Cruz County Historical Trust, one of the two groups that founded the Museum of Art and History. I went through every file that I could find on Aptos and made copies. It was a great resource. One day I came across a newspaper article about an archeological dig that took place in Aptos Village as part of the future Aptos Station Shopping Center development. One of the digs was the trash pit from the Chinese bunkhouse next to the old apple dryer building. The article showed a striking Chinese earthenware soya sauce jar discovered in the pit, (yes, I know we call it soy sauce).

I was fascinated. Where did this wind up? Surely it was in a museum somewhere. I started asking questions and eventually found archeologist Rob Edwards, an instructor at Cabrillo College, who gave me a copy of the report on the dig. I called the archeologist in Salinas who prepared the report and he put me in touch with Janice Whitlow, the person who wrote her senior anthropology thesis about the artifacts in the pit. So, I called Janice and asked her what happened to the soya sauce jar. Amazingly, she said all of the articles from the dig were in seven large boxes in her basement and that I could have them for the museum if I would keep everything together and not just keep “the good stuff”. She also would give me a copy of her thesis which identified every article. I HAD STRUCK GOLD!

The artifacts were a combination of Chinese and Euro-American ceramics and bottles that date to the first decade of the twentieth century, primarily overseas Chinese goods, including stoneware food storage vessels, porcelain rice and serving bowls, chopsticks, porcelain soup spoons, medicine bottles, and canning jars from San Francisco Chinese grocers. Other items consisted of rusted cans, an imported Australian pickle jar, and one-half of a white ironstone saucer from Knowles, Taylor, and Knowles, an American pottery firm. The beverage bottles for soda and spirits included hand blown cork type and mold made screw cap types. One very interesting item was a ginger ale bottle from Belfast, Ireland, blow-molded in aqua glass and hand finished. The round bottom was designed so the bottle would have to be kept on its side, keeping the bottle’s cork wet in order to keep in the carbonation.

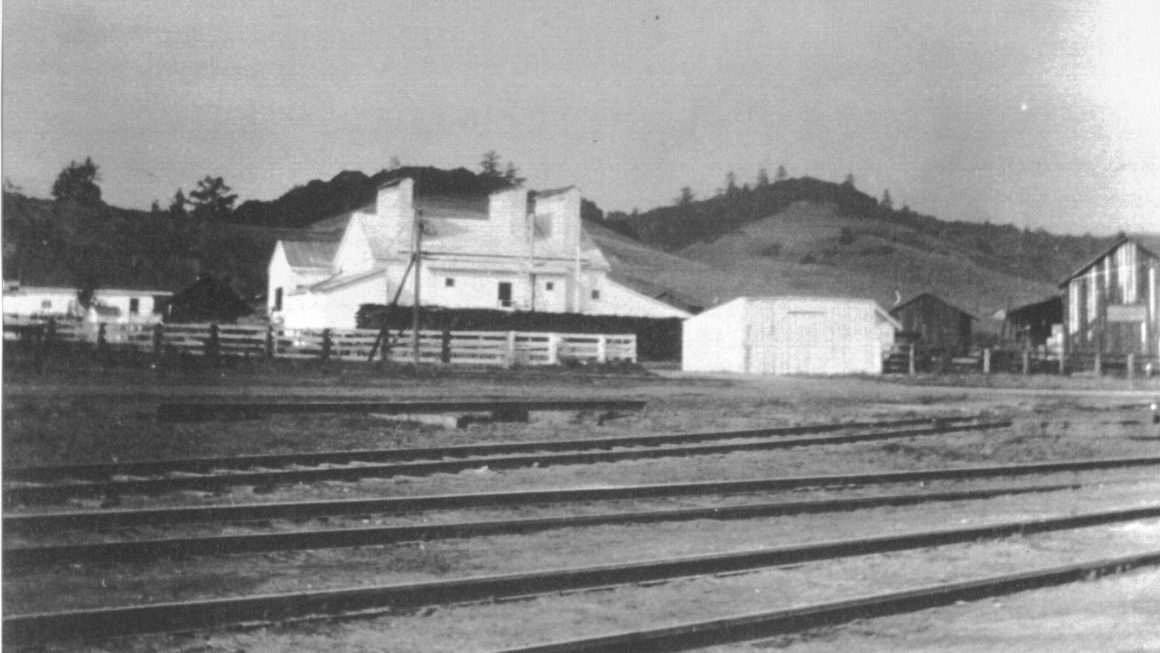

The Chinese bunkhouse was built for the seasonal laborers who worked at the apple dryer in Aptos Village. The apple dryer was built by Lam Pon, (last name first) a Chinese man who came to California before the turn of the last century. He worked as a cook and laundryman in Santa Cruz. Apples were the major industry at that time in Aptos and Lam Pon, at age 19, formed a partnership with Ralph Mattison and built an apple dryer. Lam Pon owned a share of the business but he could not own the land. Chinese were not allowed to own property outright. Lam Pon and Ralph Mattison formed a life-long friendship.

In the fall, during the apple-drying season, the Lam family would reside in Aptos.

Chinese laborers would move into the bunkhouse next to the dryer. The bunkhouse had a kitchen with large woks, and bunks were stacked to the ceiling along both walls. The bunkhouse once held 125 workers, but 35 to 40 became the norm. This is where the trash pit was located.

Lam Pon was very successful and by late 1917 the newspaper jealously noted that he had purchased a Dodge Brothers touring Car. In the 1920s, Lam Pon opened the first Chinese restaurant in Santa Cruz and a small Chinese bank. Lam Pon was successful financially but grew tired of the discrimination and the anti-Chinese laws, so by 1930 he moved his family back to China.

We learn something new, (or old), every day at the museum. Visit the Aptos History Museum and view “the good stuff” from the whole Chinese collection.

Aptos is an amazing place and so is the museum. We have put it all together for you and your children. Please consider purchasing a membership so that we can keep the doors open for your kid’s kids.