By John Hibble

When and why did the railroad come to Santa Cruz County? Who built it? What has been its impact and what will it mean to our future?

Setting the Stage

In the early days, travel between Monterey and Santa Cruz might be by foot, horse, ox cart, horse drawn wagon, or buggy. Crossing any of the 20 creeks, gullies, and sloughs in Santa Cruz County meant that you had to find a way from the high coastal plain down through the stream bed and up the other side. Many were impassible in winter. At that time Aptos was a large cattle ranch producing hides for the leather tanneries.

The first bridge over Aptos Creek was built in 1860 which allowed regular stage service usually provided by McLaughlin’s daily Concord Coaches. The first general store in Aptos was not built until 1867 on the western side of Aptos Creek. The building still exists on Wharf Road. By 1869, Live Oak House was built in Aptos on the eastern side of Aptos Creek, as a stage stop, hotel and saloon located where O’Neill Surf Shop and Post Office Drive are today.

The only practical way to move goods and freight was by ship so wharves were built at Santa Cruz, Soquel, Aptos, Pajaro, Moss Landing and Monterey. Leather, black powder, produce, small amounts of lumber, firewood and lime were the primary cargos.

Railroad Fever

In the early 1860s, the Central Pacific Railroad was working to complete the western end of the Transcontinental Railroad. The Central Pacific was owned by Leland Stanford, lawyer and wholesale merchant; Collis Huntington, merchant; Charles Crocker, blacksmith, farmer, and sawyer; and Mark Hopkins, wholesale grocer and hardware merchant. These people became known as “The Big Four”. The golden spike completing the Transcontinental Railroad was driven May 10, 1869

In 1865 the Southern Pacific Railroad Company was incorporated to build a rail line between San Francisco and the Southern California-Arizona border. The original map indicated the line would be routed along the coast to Santa Cruz, on to Aptos, over to Watsonville and then south down the Salinas Valley.

By 1868, hopes for the Southern Pacific rail line through Santa Cruz County had been abandoned. The Southern Pacific had been taken over by the Central Pacific. The planned route was now south from San Jose to Gilroy, then to Hollister and Bakersfield. A line was also planned to be built from Gilroy to Pajaro and on to Salinas. Gravel ballast for this line was provided by the new Granite Rock quarry in Aromas. On November 21st, 1871, the first broad-gauge train arrived in Pajaro for the return trip to San Francisco.

From 1865 on, men of means in Santa Cruz discussed the need for a railroad into Santa Cruz County to get the wheels of industry and commerce moving.

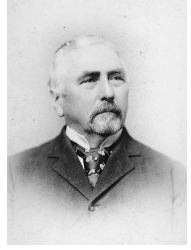

Frederick Hihn, (Heen), Santa Cruz’s first self-made millionaire, made his money as a merchant and in real estate. (Many of the millionaires at that time had made their money as merchants, mostly in food and hardware). Hihn was also the State Assemblyman for Santa Cruz County. In 1869, Hihn helped to organize a railroad committee to discuss their options. After much debate, county voters came out in support of the Santa Cruz & Watsonville Railroad bond measure in 1871. The idea was that the County would finance the line and the Southern Pacific would take it over. The vote was not supported by those in Watsonville as they already had access to the Southern Pacific Railroad in Pajaro.

On January 18th, 1872, the Santa Cruz and Watsonville Railroad Company filed formal Articles of Incorporation. On the same day, the Santa Cruz County Board of Supervisors awarded the contract and the $100,000 subsidy to the Santa Cruz and Watsonville Railroad Company to build the road. The significant conditions in the contract were that the construction would start within six months and be completed within two years and, in order to show good faith, five miles of right-of-way would have to be completed before the first portion of the $5,000 per mile subsidy would be awarded.

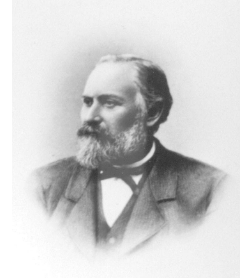

Leland Stanford came to Santa Cruz to say the Southern Pacific wanted to build the road and started surveying the route, but Southern Pacific found itself over-extended and cancelled plans to be part of the Santa Cruz to Watsonville line. About the same time, Claus Spreckels, the sugar multi-millionaire from San Francisco bought 2,600 acres of the Aptos Rancho east of Aptos Creek for a ranch and summer home.

By June 1873, Claus Spreckels and F.A. Hihn helped convince Santa Cruz County businessmen to build the railroad themselves. Due to costs, it would have to be a narrow-gauge (36 inch) line. Funds for the new Santa Cruz Railroad project included their own monies plus the previously approved county subsidy. December 29th the first rail was laid, and construction worked from Santa Cruz toward Watsonville.

The majority of laborers on the line were Chinese. The right of way for the line was primarily along the coast except that when it reached Aptos, it swung inland across Aptos Creek and then back to the coast across Valencia Creek. This diversion opened up properties owned by Hihn and Spreckels for future development.

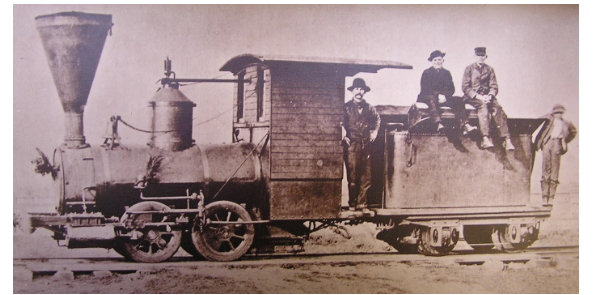

In October 1874, the Betsy Jane, a tiny construction locomotive, arrived. It was designed in Santa Cruz and built in San Francisco. Betsy Jane was the work engine used to build the railroad. After the Santa Cruz Rail Road was completed and the full sized passenger and freight engines arrived, the Betsy Jane went to work for a lumber company. The people in Watsonville referred to her as a “Tea Kettle.”

Four miles of used rail were purchased in San Francisco and spiked down while awaiting the arrival of new rail from the east coast. The ship carrying the rail sunk off Bolivia and the ship carrying the second load of rail caught fire off Bolivia delaying construction by eight months. More expensive replacement rail was ordered from San Francisco.

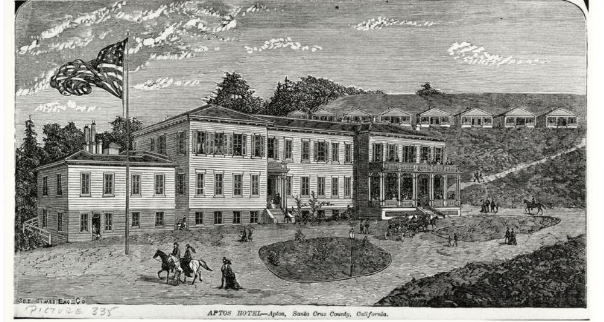

On December 7, 1874, the first five miles of Santa Cruz Railroad track were completed and Hihn asked the county for payment. One week later, Watsonville attorneys secured an injunction to stop payment of county funds because the line was not going to pass through the city of Watsonville. The Watsonville City Council had voted against giving the S.C.R.R. a street franchise through town to the Pajaro River. As a result, the railroad had decided the final alignment of the right-of-way into Pajaro would be about a half-mile west of Watsonville. Construction continued, eventually with an infusion of cash from Spreckels. Meanwhile, Claus Spreckels was also building a first-class hotel in Aptos overlooking the bay.

On May 22, 1875, fifty-cent excursion service began on the weekends between Santa Cruz and Aptos. The Grand Opening reception was held for the Aptos Hotel built by Claus Spreckels. Spreckels Drive was the private entrance road. The event included a ball attended by Governor Romualdo Pacheco and celebrated the formal opening of the Santa Cruz Narrow Gauge Rail Road to Aptos. (Pacheco remains the only Hispanic governor in the state’s history, as part of the U.S.A. He was also the state’s first governor to be born in California.) Everyone who was anyone was at the event. The happy revelers literally danced all night, till broad daylight, the party not braking up till half past four A.M.. A splendid supper was had at 12 o’clock. The dining room being of limited capacity, only 25 x 60 feet, the tables had to be set three separate times. The hotel had all of the latest improvements including indoor plumbing and gas lights, a bowling alley, billiard room, riding stables and a promenade. It was the finest summer resort hotel in California.

A second grand ball was held one a week later at the Pacific Ocean House in Santa Cruz,

On June 6th, three trains from Santa Cruz brought over 1,000 people, plus another 500 by private conveyance, to the dedication picnic for Spreckels’ Aptos Hotel. The combined Red Men and Druids of Santa Cruz held a picnic celebrating their anniversary. A special stockholders meeting was held to try and sell additional stock to raise money to complete the rail line.

Work progressed on the line toward Pajaro, but a disastrous winter slowed progress. By March 1876, Hihn and Spreckels had agreed to adjust the route into Watsonville and the injunction was lifted.

In April 1876, Santa Cruz Rail Road’s Watsonville- Santa Cruz line was completed, and the Betsy Jane locomotive delivered the first revenue load, two carloads of potatoes!

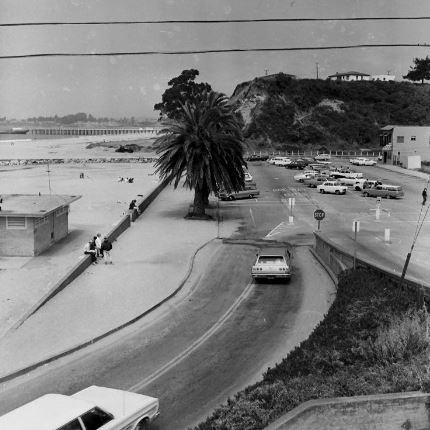

Finally, on May 7th, 1876, the long-awaited day had come. For the first time in the history of Santa Cruz County, a passenger train was about to run from Pajaro via Watsonville, Aptos, and Camp Capitola to Santa Cruz.

The Pacific, a brand-new narrow gauge 4-4-0 Baldwin steam engine had just been delivered to the S.C.R.R. at Pajaro. It was hooked up to the railroad’s first coach, “the Teresa,” named after F.A. Hihn’s wife and was waiting to take passengers to Aptos to meet the train from Santa Cruz.

The Druids had scheduled their annual picnic at Aptos to fall on this historic day. Not only was Santa Cruz County celebrating the coming of the railroad, but also the nation’s centennial. In Santa Cruz, over two hundred people were awaiting the departure of the first of two trains that would take them to Aptos. The Betsy Jane was pulling five colorful makeshift cars, all decorated in red, white, and blue ribbons and banners, with an abundance of flowers and flags.

At 9:30 a.m., the Betsy Jane approached Aptos at the breakneck speed of 15 miles per hour. By 11:30 a.m. the Betsy Jane had completed its second trip to Aptos.

Around noon someone shouted, “I heard a whistle”! Distant thunder began to fill the warm afternoon air. This was it, the occasion that everyone had come to celebrate. Bill Holser, fireman, made a mad dash for the Betsy Jane. He grabbed the whistle cord and commenced to blow long, continuous blasts. In return, the same long continuous blasts were heard in the distance. Soon, all of the people were gathered trackside. Bells were ringing, whistles blowing, crowds were cheering. The air was shattering with mighty explosions from the cylinders of some monstrous steam locomotive approaching from the East. In an instant, as if no time had passed at all, a plume of dark smoke was seen filtering through the trees in the direction of the Valencia Creek bridge. People were shouting, little children were crying, tears of joy streamed the faces of many onlookers. And then, all at once, there it was. The most beautiful 22-ton piece of steam power ever to be seen in Santa Cruz County, with its equally lavish coach, came charging out of the trees and across the bridge toward the crowd at Aptos. Oh, what a sight to behold as the gallant Pacific, its boiler panting in unison to the geometrical sounds that were being emitted from its drivers, gently slowed to a stop among the crowd. Inch by inch it worked its way forward, until at last it touched noses with the prideful little Betsy Jane; all at once, the Santa Cruz Rail Road was a reality. Hats flew, guns went off, the air was filled with the ear-shattering sounds of bells and steam whistles and screaming voices. It was as if the completion of the transcontinental railroad, rather than a little 21 – mile narrow-gauge operation, was being celebrated for the very first time. Santa Cruz County had come of age.

In 1877, the second locomotive Jupiter was delivered. It is now in the Smithsonian as part of their transportation exhibit.

From 1876 to 1880, the Santa Cruz Rail Road did reasonably well financially, but was hindered by the competition with the Southern Pacific Railroad at Pajaro. Being a smaller gauge than the Southern Pacific meant that cars were not interchangeable, and all freight and passengers had to be transferred to different trains at Pajaro. In 1880 the over-the-mountain South Pacific Coast Railroad was completed to Santa Cruz.

The Pacific Coast Steamship Company was also offering better freight rates in Santa Cruz; therefore, the railroad line saw very little freight business.

The construction costs for the Santa Cruz Rail Road exceeded $591,000, over twice what F.A. Hihn had estimated. By that time, Hihn was paying the expenses out of his own pocket. Finally, in February 1881, the trestle over the San Lorenzo River was brought down in a flood. Hihn, Spreckels and other stockholders were no longer willing to subsidize operations in the face of competition with the South Pacific Coast and Southern Pacific Railroads. The Santa Cruz Rail Road went into bankruptcy.

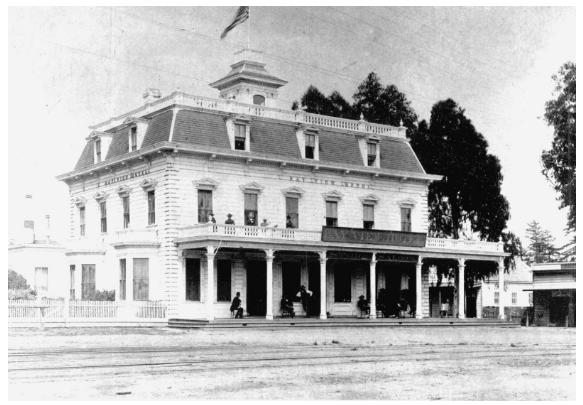

Within this time frame The Anchor House, (Bay View Hotel), was built in the new Aptos Village on the east side of Aptos Creek. A Chinese fishing camp had been established at China Beach (New Brighton) with 29 fishermen and by 1878, they shipped 177,000 lbs. of fish on the train. Camp San Jose visitor campground opened on the bluff at New Brighton Beach forcing the Chinese fisherman to move down the coast toward Aptos Creek. And in 1880 Hotel Del Monte opened in Monterey. It was built and serviced by the Southern Pacific Railroad, and it competed with Spreckels’ Aptos Hotel.

Consolidation

In October 1881, the Southern Pacific bought the Santa Cruz Railroad at auction and began laying standard-gauge track which was completed by September 1883. The two years of construction severely affected access to Spreckels’ Aptos Hotel. The narrow-gauge locomotives were moved to other locations (e.g., the Jupiter was sent to Guatemala to transport bananas).

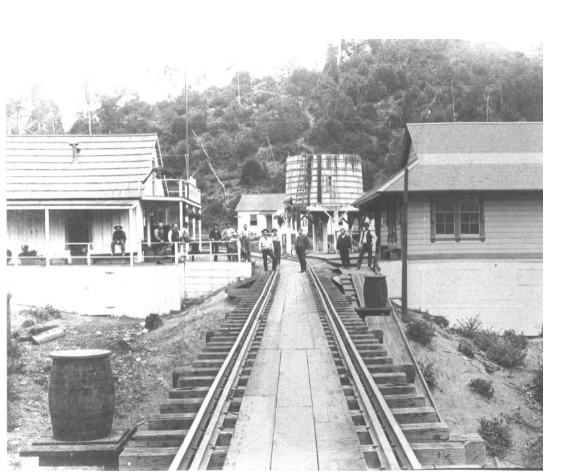

As soon as standard-gauge track reached Aptos, Southern Pacific built a spur line into Aptos Creek Canyon to harvest the timber. It was the most expensive rail line that they had ever constructed. Loma Prieta town was built including a sawmill, post office, express office, stores, cabins, and a hotel. The town grew to 185 residents and the mill was expanded to produce 140,000 board feet of lumber per day at full production.

In May of 1883, Frederick Hihn’s Aptos Mill opened on Trout Gulch Creek, just above its junction with Valencia Creek. It was capable of producing 30 to 40 thousand board-feet of lumber per day. The mill was moved to Valencia in 1885. During the lumber era from 1883 to 1923 most of the Santa Cruz Mountains were stripped of all available timber.

In January of 1887, Southern Pacific bought the over-the-mountain South Pacific Coast Railroad and controlled Santa Cruz County’s two main railroad lines promoting tourism and industries.

In 1888, Spreckels opened the largest beet sugar factory in North America in Watsonville using the railroad to haul the raw and finished product. The factory helped Watsonville to weather the depression of the 1890s.

In 1903, President Theodore Roosevelt visited Santa Cruz County by train.

By 1918 there were 18 passenger, and six freight trains a day arriving and departing Santa Cruz. Trains also provided transportation for high school students. The direction of the morning train determined which high school you went to. Most students in Aptos took the morning train to Watsonville.

In the 1920s, after the lumber played out, apples became the next big agricultural commodity to rely on rail transportation.

In 1927, Southern Pacific began the Suntan Special, an excursion train over the mountain from San Jose to the beach in Santa Cruz. The late 1930s were the most popular years of the Suntan Special. It was not uncommon to have 5,000 riders a day. A round trip cost $1.25. At least one train also ran each operating day along the coast to Watsonville Junction to drop passengers off at Seabright, Capitola, and Aptos. The excursion train was suspended during World War II.

Regular passenger service on the Santa Cruz Branch Line was suspended in 1938 and the Aptos train station was torn down in 1940. That same year, a storm closed the over-the-mountain rail line, and it was eventually abandoned. In April of 1940, the Suntan Special resumed, going around-the-mountain through Watsonville Junction to Santa Cruz, adding 35 minutes to the trip.

From July 1947 until September 1959, the Suntan Special continued during the summer carrying about 900 passengers per trip.

On Sunday, May 7, 1976, a 100-year anniversary commemoration was held with the cooperation of Southern Pacific Railroad and the Chambers of Commerce of Watsonville, Aptos, and Santa Cruz. It began at Watsonville Junction at 9 a.m., with a ribbon cutting, followed by a 9:30 stop at Aptos, and then a ceremony at the Santa Cruz Depot from 11:30 to 12:30 p.m. and a 1:30 p.m. ceremony at Felton’s Roaring Camp.

In 1996, Union Pacific Railroad bought the Watsonville-Santa Cruz line.

On October 12, 2012, the Santa Cruz County Regional Transportation Commission completed acquisition of the Santa Cruz Branch line which is now owned by the people of Santa Cruz County. The rail right of way is now planned to include a pedestrian/bicycle trail and passenger service in the future. It will be interesting to see what role the rail trail plays in our future given the lack of transportation alternatives.

Much of this information was gathered from “California Central Coast Railways” by the late Rick Hamman, with permission.

May 2018, revised June 2021